Article 8 of the Paris Agreement – Exploring potentials for Africa: Review of the guest editorial in Climate Policy 2020, Vol. 20, No. 6, 661-668

https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1778885

Chijioke Kelechi Iwuamadi

PhD (Nsukka, Nigeria)

Advisor, the Deutsche Gesellschaft fuer Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH African Union Office, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0001-9087-2328

Edition: AJCLJ Volume 1 2024

Pages: 160 - 167

Citation: CK Iwuamadi ‘Article 8 of the Paris Agreement – Exploring potentials for Africa: Review of the guest editorial in Climate Policy 2020, Vol. 20, No. 6, 661-668’ (2024) 1 African Journal of Climate Law and Justice 160-167

https://doi.org/10.29053/ajclj.v1i1.0008

Download article in PDF

Abstract: This is an analytical review of the guest editorial in Climate Policy 2020, Vol. 20, No. 6, 661-668, https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1778885. The review is timely as it generally contributes to the global discourse towards deepening the debate on Loss and Damage (L&D) occasioned by climate change. The review paper argues that many countries of the Global South, including Africa are yet to harness the benefits of climate finance to address the effects of loss and damage, as a result of minimal efforts made towards reducing the risks and harms on the continent. Thus, there is an urgent need to further expose states in Africa to innovative mechanisms of addressing the challenge of L&D. Effective collaboration and collective responsibility are paramount and can be achieved through civic engagement and knowledge sharing on domestic policies and global instruments.

Key words: civic engagement; climate change; climate finance; loss and damage

1 Introduction

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in 2020 reported that ‘if no urgent action is taken, the number of people in need of humanitarian assistance due to the climate crisis could double by 2050’. The IFRC further estimated that the financial costs to respond to these crises would grow from US $3,5 to US $12 billion to US $20 billion per year by 2030.1 Africa remains vulnerable in this global outlook on the expected humanitarian crisis caused by climate change. The collaboration between governments and civil society actors over the years in addressing the climate governance crisis in Africa has not adequately utilised global opportunities that mitigate climate change loss and damage (L&D). African state actors and their global partners are aware of the L&D associated with the effects of climate change, yet minimal efforts are made towards reducing the risks and harms on the continent. What global opportunities are available for addressing economic and non-economic L&D caused by climate change? As the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) reiterated, ‘the Paris Agreement’s targets to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius’.2 How could enhanced joint partnerships amplify awareness about the application and domestication of article 8 of the Paris Agreement to ensure reparation and repairs of the impact of climate change?3

This article argues that effective collaboration and collective responsibility can be achieved through civic engagement and knowledge sharing on domestic policies and global instruments. One can achieve the desired results by harnessing opportunities that address issues of L&D arising from climate change. This review further reinforces the needed approach that could address the gaps identified by Broberg and Romera in the editorial with regard to the adoption of the L&D (article 8) during the 2015 Paris Agreement without a substantive framework of implementation, using the two authors’ bone and flesh analogy.

2 Distinction between adaptation and loss and damage

Meanwhile, the trajectory of the provision of article 8 of the Paris Agreement could be traced to the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) which was revisited at the 21st Conference of the Parties (CoP) in 2015 and finally resulted in the inclusion of a L&D article in the Paris Agreement. Nevertheless, there were some concerns about the legal and policy implications for state parties’ responsibilities for L&D, given the dwindling global economy particularly as it affects developing countries. To address this challenge, Emma Lees was of the view that for climate L&D as provided in article 8 of the Paris Agreement to be relevant, there is ‘the need to develop policy which is sensitive to the fine balance struck in the Paris Agreement between responsibility and liability for L&D and prompts an open discussion as to how such responsibility ought to be allocated’.4 There was also the contestation about the need for clarity on climate change L&D versus climate change mitigation and adaptation.

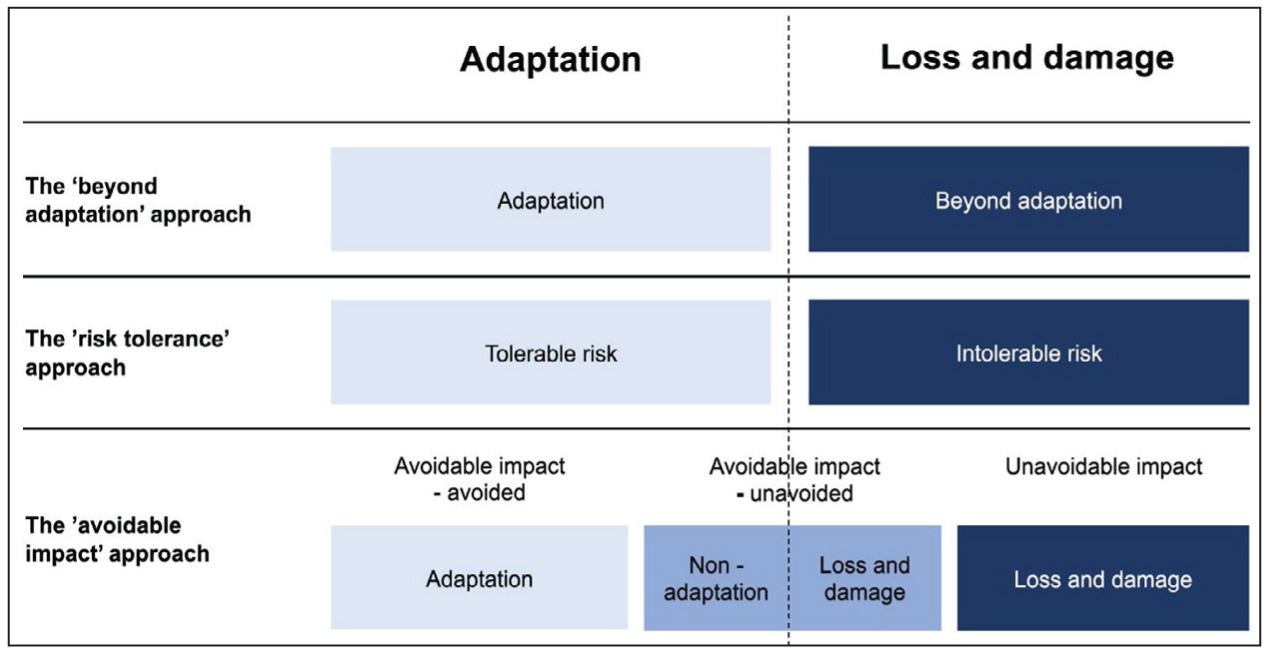

On clarity regarding climate change L&D, Broberg and Romera in the editorial posed some puzzles that distinguish the provision of article 8 during the adoption of the Paris Agreement. They raised the important question of the distinction between L&D, and adaptation, and the legal implications of the inclusion of L&D as an article in the United Nations (UN) Climate Change instruments. They further demonstrated in the matrix (Figure 1) below, graphically explaining the three most common ways of distinguishing adaptation and L&D.

Figure 1: The three most common ways of distinguishing ‘adaptation’ and ‘loss and damage’

The graphic meaning in Figure 1 above as presented by Broberg and Romera was to help fill the gap of lack of a clear formal definition of L&D by ‘neither the Paris Agreement nor the UN climate change treaty regime’. This in their opinion has led to both practitioners and academics applying diverging definitions that can broadly be divided into three different groups as they are shown in Figure 1. According to Broberg and Romera, the initial definition is that L&D cover measures that address the impacts of climate change that are ‘residual’ to mitigation and adaptation. Here, integrated ‘insufficient mitigation’ with ‘inadequate adaptation’ results in L&D. Thus, some other scholars agree that constructing L&D in this way is referred to as the ‘beyond adaptation approach’.5

Another definition Broberg and Romera presented in the above matrix (Figure1) focuses on what they considered to be the ‘tolerable risk’. Here, according to them, adaptation is about keeping risks within the range of what is perceived as ‘tolerable’, whereas L&D are a response to risks that cannot be kept within that range.6 The other definition in the matrix, as they defined L&D, is by distinguishing between climate change impacts that are ‘avoidable’, ‘unavoidable’, or ‘unavoided’. Here, they argued that ‘if it is impossible to adapt to an impact so that it becomes unavoidable, it will fall in the L&D category’. They further expressed that ‘for impacts that are avoidable, it is necessary to distinguish between those that are avoided and those that are not. If it is possible to adapt to an avoidable impact so that it is avoided, this is a case of adaptation’. On the flip-side, they noted that ‘if an avoidable impact is not avoided, it is unclear from this definition whether it is to be categorised as (non-) adaptation, or as L&D’.7

Considering the uncertainties or what could be perceived as controversies in the above matrix and definitions due to no universal or accepted interpretation of L&D, it is imperative for the Global South, particularly Africa, to have a home-grown definition based on peculiarities and diverse effects of economic and non-economic L&D.

3 Loss and damage provision in article 8 of the Paris Agreement

Okereke, Baral and Dagnet highlighted the point that the concept of L&D has always been implicit in the UNFCCC but serious negotiations and concrete outcomes surfaced over the years. For them, ‘the issue of L&D re-emerged gaining significant attention, unlike adaptation, which took almost a decade to be fully incorporated into UNFCCC negotiations, the issue of L&D gained real traction over a relatively short period of time’,8 whereas, Broberg and Romera in the editorial expressed that the inclusion of article 8 in the Paris Agreement,9 introduced into treaty law a longstanding process for the recognition of L&D in the climate change regime. The authors noted that this process started in 1991 when the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) ignited discussions with a proposal for the introduction of a mechanism to address climate change L&D (Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee for a Framework Convention on Climate Change (INC)) during the negotiations that led to the adoption of the UNFCCC in 1992.10 Ironically, specific emphasis on the effects of climate change L&D on Africa, except the Caribbeans and high-income regions, was missing; rather, the attention was on the Global South in general.

The corollary of the above, therefore, suggests a more deepened understanding of how the issue of L&D as it affects Africa has been handled within the UN system. Sharma demonstrated that ‘the interests of the poorest countries, communities and individuals and the most vulnerable are inadequately accommodated in the Paris Agreement’. The argument here is that the Paris Agreement does not satisfy the provisions of UNFCCC article 3.3, which calls for a precautionary approach to addressing the adverse effects of climate change. Further action is needed to strengthen the provisions on mitigation and dealing with the impacts of climate change in the face of uncertainty.11 Regrettably, this is the reality in Africa where liability and state responsibility have become a threat to addressing the issues of L&D.

4 Challenges of climate change loss and damage

Adequate knowledge and means of accessibility of climate finance for L&D is yet to be maximised across the least developed countries. The limited knowledge about climate finance for L&D has resulted in perpetual ignorance of the vulnerable in developing countries and victims of L&D. There is a need for more awareness and reflections on climate L&D beyond climate adaptation. This, therefore, calls for the reorientation of national and sub-national governments, civil society organisations, and all relevant stakeholders to recognise the growing need to collectively address climate L&D.

Broberg and Romera identified what they referred to as the key gaps in L&D governance: non-economic L&D and slow-onset events. In their view, ‘efforts in addressing L&D are often primarily circumscribed to insurance approaches that target economic losses: non-economic L&D (including loss of knowledge, social cohesion, identity, or cultural heritage) as well as slow onset events are largely left unaddressed’. In the case of the small island developing states (SIDs) in the Caribbean, as narrated in the editorial, the 2017 hurricane season brought the issue of L&D to the fore when two category five storms passed through the region within two weeks of each other, resulting in severe damage on many islands.12

The above argument on economic loss versus non-economic loss in the context of climate change L&D governance should be a concern, particularly in Africa where insurance policy has been receiving inadequate patronage across the continent at an all-time low. Despite the advantages of insurance policy, Africa’s aggregate insurance penetration rate in 2019 was only 2,78 per cent, compared to the global average insurance penetration rate of 7,23 per cent.13 On the one hand, with regard to insurance schemes, Broberg and Romera are of the view that insurance is one of the avenues through which it may be possible to seek remedies for L&D. In this situation, they were of the view that a parametric insurance scheme should be explored because, unlike conventional insurance schemes, it is relatively straightforward to establish objectively whether the conditions for payment have been fulfilled and not necessarily based on assessment.

On the other hand, the authors highlighted Nordlander and others’ critically review of the limitations of what they term ‘active insurance schemes for L&D’. They contend that despite the popularity of insurance schemes among policy makers, the potential for insurance schemes to deliver appropriate financial responses to L&D is limited. For them, insurance schemes are fundamentally misaligned with the founding principles of the international climate change regime.14 In the Global South, beyond the push for expanding Africa’s insurance market and making it lucrative for inclusive prosperity, there is a need to examine the non-economic L&D resulting from climate change. The lack of social safety nets and programmes that provide palliatives or shock absorbers for victims who lost their identities, cultural heritage, and suffered mental health issues, among others, has remained an obstacle to inclusivity of addressing the non-economic L&D.

The other vital point to note in the editorial is the challenge of L&D litigation. In as much as successful litigation remains an avenue for compensation under L&D, how independent are the domestic justice and legal systems in developing countries? How knowledgeable are the human rights defenders and lawyers on issues of L&D? As cited in the editorial by Broberg and Romera, there is a first set of legal questions coalescing around the topic of L&D litigation, in the context of whether article 8 of the Paris Agreement may be used to force action in order to address L&D from climate change. The complexity of the multilateral approach needed to legally address climate change L&D positions developing countries on the disadvantaged and dependent side due to lack of adequate knowledge and capacity to litigate and negotiate on issues of L&D.

5 Opportunities for mitigating effects of climate change loss and damage

In the context of novel approaches to L&D, Broberg and Romera observed ‘the potential of human rights law, and human rights approaches to provide remedies and thereby fill gaps in the field of climate change law and litigation where other areas of the law do not’. Their argument here is based on the extant literature that labelled climate change as human rights challenge and, in particular, L&D resulting from climate change pose a severe threat to the human rights of affected communities. Remarkably, they further acknowledged the recognition of human rights under the UNFCCC but with an insufficient level of integration of human rights in international climate governance.15

Deducing from the review of the editorial by Broberg and Romera, many opportunities duly emerge. For instance, the authors posited that framing L&D through the lenses of human rights and obligations and adopting a human rights-based approach could strengthen the international response to L&D. Accordingly, they reiterated that a human rights-based approach to L&D could remedy the framing of L&D in abstract, state-centric terms as a developing country issue. It could put the spotlight on the fundamental human rights of the individual, including consideration of the intersectionality of L&D impacts, with, among others, questions of race, gender, class, age, and economic well-being.16

A review of the aforementioned opportunities using the human rights-based approach presented by Bromberg and Romera further suggests that to effectively address the issue of climate change L&D in Africa, the African Union (AU) human rights system and national human rights institutions require an integrated and collaborative engagement with the civil society actors to further explore and institutionalise legal infrastructure that seeks to address climate change L&D, especially in the areas of compensation and reparation. There is also a need to reinforce psycho-social support systems that would provide succor to victims of mental health resulting from non-economic L&D.

6 Conclusion

As part of global measures of applying climate finance, COP2717 in 2022 established a Loss and Damage Fund to respond to the human cost of climate change. This fund, among others, is to support governments to rebuild or rehabilitate communities, health centres, roads, and provide social protection, and so forth, that were damaged or lost by weather events and climate disasters. In more than one year now, how many countries of the Global South, including Africa, have benefited from or even set up required modalities or mechanisms for accessing the fund? Are vulnerable African citizens aware of this fund?

As Broberg and Romera rightly observed, ‘with the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement, the notion of L&D was given a formal platform within the UN climate change treaty regime’. They reiterate that, whereas article 8 of the Agreement provided the bones for a L&D scheme, there was still an obvious need to put flesh to these bones. In the context of Africa, which was not emphasised in the editorial, this review essay opines that knowledge about L&D in article 8 of the Paris Agreement has not been disseminated and domesticated among many African states. Therefore, there is an urgent need to expose the African continent to innovative ways beyond litigation and negotiation, of addressing the challenge of L&D resulting from climate change.

The lack of adequate knowledge and capacity of states, sub-national government actors and non-state actors, including civil society actors, has continued to make it difficult for developing countries, particularly in Africa, to explore opportunities provided by litigation and negotiations in addressing economic and non-economic L&D occasioned by climate change. Improvement in communication and information sharing in relation to domestic legal and justice systems is paramount in positioning victims of L&D to be able to access avenues of climate finance for their compensation. Continuous intensive advocacy and training for human rights defenders, lawyers and judges are also very key in facilitating the actualisation of litigation on L&D.

1 IFRC ‘World disasters report’ (2020), https://www.ifrc.org/document/world-disasters-report-2020 (accessed 15 September 2023); M Broberg & BM Romera ‘Loss and damage after Paris: More bark than bite?’ (2020) 20 Climate Policy 661.

2 Key aspects of the Paris Agreement | UNFCCC (accessed 1 August 2024)

3 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change CP/2015/10/Add.1 29 January 2016 Decision 1/CP.21 adoption of the Paris Agreement.

4 E Lees ‘Responsibility and liability for climate loss and damage after Paris’ in J Depledge and others (eds) Climate policy after the 2015 Paris Climate Conference (2021), https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003191582-7/responsibility-liability-climate-loss-damage-paris-emma-lees?context=ubx (accessed 2 September 2023).

5 R Mechler and others ‘Science for loss and damage: Findings and propositions’ in L Mechler and others (eds) Loss and damage from climate change: Concepts, methods and policy options (2019) 3-37.

6 K Dow and others ‘Limits to adaptation’ (2013) Nature Climate Change 305-306, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1847 (accessed 2 September 2023).

7 K van der Geest & K Warner ‘Loss and damage in the IPCC fifth assessment report (Working Group II): A text-mining analysis’ (2019) Climate Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1704678 (accessed 13 September 2023).

8 C Okereke, P Baral & Y Dagnet ‘Options for adaptation and loss & damage in a 2015 Climate Agreement’ (2014) Researchgate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268446419_Options_for_Adaptation_and_Loss_Damage_in_a_2015_Climate_Agreement (accessed

2 September 2023).

9 Paris Agreement (n 4).

10 Broberg & Romera (n 1) 661.

11 A Sharma ‘Precaution and post-caution in the Paris Agreement: adaptation, loss and damage and finance’ Climate Policy (2017) 17(1) 33.

12 Broberg & Romera (n 1) 665.

13 Brookings ‘Capturing Africa’s insurance potential for shared prosperity’ (2 July 2021), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/capturing-africas-insurance-potential-for-shared-prosperity/ (accessed 27 September 2023).

14 L Nordlander, M Pill & BM Romera ‘Insurance schemes for loss and damage: Fools’ gold?’ (2019) Climate Policy, https:// doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1671163 (accessed 5 Sep-tember 2023).

15 Broberg & Romera (n 1) 666.

16 As above.

17 The Conference of the Parties (CoP) of the UNFCCC described the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference or Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC, also known as COP27, as the 27th United Nations Climate Change conference, held from 6 – 20 November 2022 in Egypt.

* PhD (Nsukka, Nigeria);